“He hit that ball 106 miles an hour,” the person said. “It seemed like it was a tough play.”

Miller didn’t need to see a replay. He was comfortable with his decision and told the person three innings later it would remain an error.

“That’s a terrible call,” the videographer told him. “I’ve never seen a call like that.”

“Just wait around,” Miller told him. “It’s early.”

According to the official Major League Baseball rulebook, “A fielder is given an error if, in the judgment of the official scorer, he fails to convert an out on a play that an average fielder should have made.”

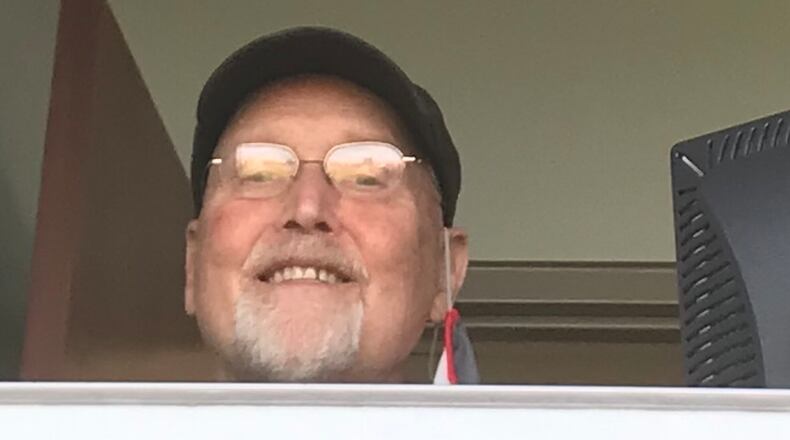

Of course, many plays fall into a grey area. It’s up to the official scorekeeper to decide what’s an error and what’s a hit. It can be a tough job. The fact that Miller, who worked about 30 Dragons games at Day Air Ballpark this year as part of a three-man scorekeeping team, was able to do it at all six years after suffering a stroke is the reason he sat down for an interview in his hometown of Springfield last week.

Credit: Ron Alvey

Credit: Ron Alvey

The new normal

In October 2015, Miller dropped a glass of water in the evening and thought he was slurring his words. He looked at himself in the mirror and didn’t think anything was wrong. His wife, Connie, did think something was wrong with him, he said, but they went to bed.

“I got up in the middle of the night like old men do to go to the bathroom and hit the floor and couldn’t get up,” Miller said. “I didn’t think it was still anything. I went to the hospital. I guess it was a biggie, and I waited too long to get there so I couldn’t take the shot or have any of the things that would have reversed it.”

Miller spent four days in the hospital and three weeks in rehab, learning how to to walk without the full use of his left side. Lift chairs were installed in his house, though he can climb stairs as long as there are handrails on the right side. He can’t use his left arm or hand, so he can’t perform some simple tasks such as tying his shoes.

Miller had to pass a test to prove he can drive, which he can do because he can reach the pedals with his right foot, and his right arm is fine. In short, he has a new normal.

“I get frustrated,” Miller said. “My language probably hasn’t been the best at times. It’s just frustrating that you can’t do some of the things that you could do since you were 2 years old.”

Credit: David Jablonski - Staff Writer

Credit: David Jablonski - Staff Writer

Perfect opportunity

Baseball has always been a big part of Miller’s life. He saw his first game at Crosley Field in 1963. He hated Ernie Banks, who hit a home run that day for the Chicago Cubs. He was crushed when the Cincinnati Reds traded Frank Robinson but enjoyed the Big Red Machine years and stayed in the game throughout his adult life after graduating from Northwestern High School.

Miller was the head coach of the Catholic Central High School baseball team and later worked as an assistant coach to Rick Woods at Southeastern. He worked for the Clark County Recreation Department from 1979 to 2009 and helped resurrect the Springfield/Clark County Baseball Hall of Fame in 2002. He also been involved in vintage baseball — the game is played by the original 1860s rules (no gloves, for example) — over the years with the Champion City Reapers.

He is now chairman of the Dayton chapter of the Society of American Baseball Research and has written four biographies on players with local connections. He has also been a member of the Dayton Dragon Friends Booster Club since the early years of the franchise.

Mark and Connie have befriended many players over the years — Jesse Winker, Hunter Greene and Billy Hamilton, for example — and remain in touch with some.

Amir Garrett and Sal Romano were among the players who reached out to Miller after his stroke. One summer, the Millers had five foreign-born Dragons live with them in Springfield, including one who made it to the Reds in 2017, Alejandro Chacín.

“We learned about new kinds of foods,” Miller said. “We learned a little Spanish, and they learned little English.”

Miller got to know Tom Nichols, the longtime broadcaster and director of media relations with the Dragons, and that’s how the opportunity to work as a scorekeeper came about. It was the perfect chance for Miller to return to work — something he never planned to do after retiring — because it’s a job he can do despite his physical limitations, and it involves the game he loves.

“There are actually three people in the booth,” Miller said. “There’s a guy that does the computer stuff for Gameday. That’s what you see on the computer if you’re following the game. Then there’s the guy that puts the balls and strikes and the runs on the scoreboard. He’s the guy that handles all the reviews. I make the calls on the hit and errors, and if it’s a tough one, I say, ‘What do you think guys?’ Mostly, they say, ‘I think it’s your call.’”

Miller knows he made the right call by accepting the Dragons’ offer. He hopes telling his story might help people in a similar situation. You just have to live with it. My grandkids still love me. They like me to come around.”

Miller has three grandchildren. The oldest, Vanessa, plays softball at the University of Louisville and appeared in 22 games last season as a freshman. The two others, Calvin and Josie, are twins. Mark’s son Matt, who played for him at Catholic Central, and his family live in Southport, Ind.

“I still help my grandson with his baseball,” Mark said. “I can’t get out there and (play with him anymore), but I can tell him what to do. He doesn’t listen to me probably anymore than he listens to anybody else, but I surprise myself sometimes because now I tell him it’s about having fun. I’m thinking, ‘Who is this guy? It’s about fun? You’re supposed to be out there try8ing to crush them.’”

About the Author